Why are they called denominations?

There is a guy named Peter Rollins who is brilliant and is also someone who I have a very difficult time understanding him. It is not because of his accent (he is Irish*) but because he is a philosopher and I am not. In a conversation I heard between him and Science Mike and Michael Gungor and Peter Rollins said something that hit me.

From what I recall, Rollins was talking about metaphor. A metaphor does both describe and negate that description simultaneously. For instance, if you described someone as having a heart of gold, you are both saying something about that person's heart while at the same time saying their heart is not a block of metal. Metaphors both affirm and negate.

The next step of the conversation was about how all language about God is metaphor. When we say God is father we are both saying something and negating something. God is like a father, but God is also not a literal father. This is the beauty of language about God, it is both helpful and limited. It gives us insight into something but it also leaves us a little lost.

We Christians have had a habit of elevating one half of the equation while dismissing the latter half. That is to say, we like the side of language that affirms (God is father) but do not like the side of language that negates (God is not father). Rollins points out that the role of religion is to move people to embrace that which is unknown and so religion needs to elevate the side of language that negates in order to help us mature.

Rollins pointed out that he likes that Christian divisions are called "denominations" - they are groups that de-name. Can we be a denomination that embraces the power of language in it's fullness? Can we be a people that is at ease with both what God is and what God is not? Can we be a people who are courageous enough to look at a situation that is done in the name of God and stand up and say in fact this action is not of God? Are we mature enough to see that God is and at the same time God is not?

Maybe this is why they are called denominations. They are groups that are trying to be mature enough to embrace the fullness of God, and not just the parts of God we can name.

* I originally identified him as Australian. I apologize to all Australians and Irish and all thinking people.

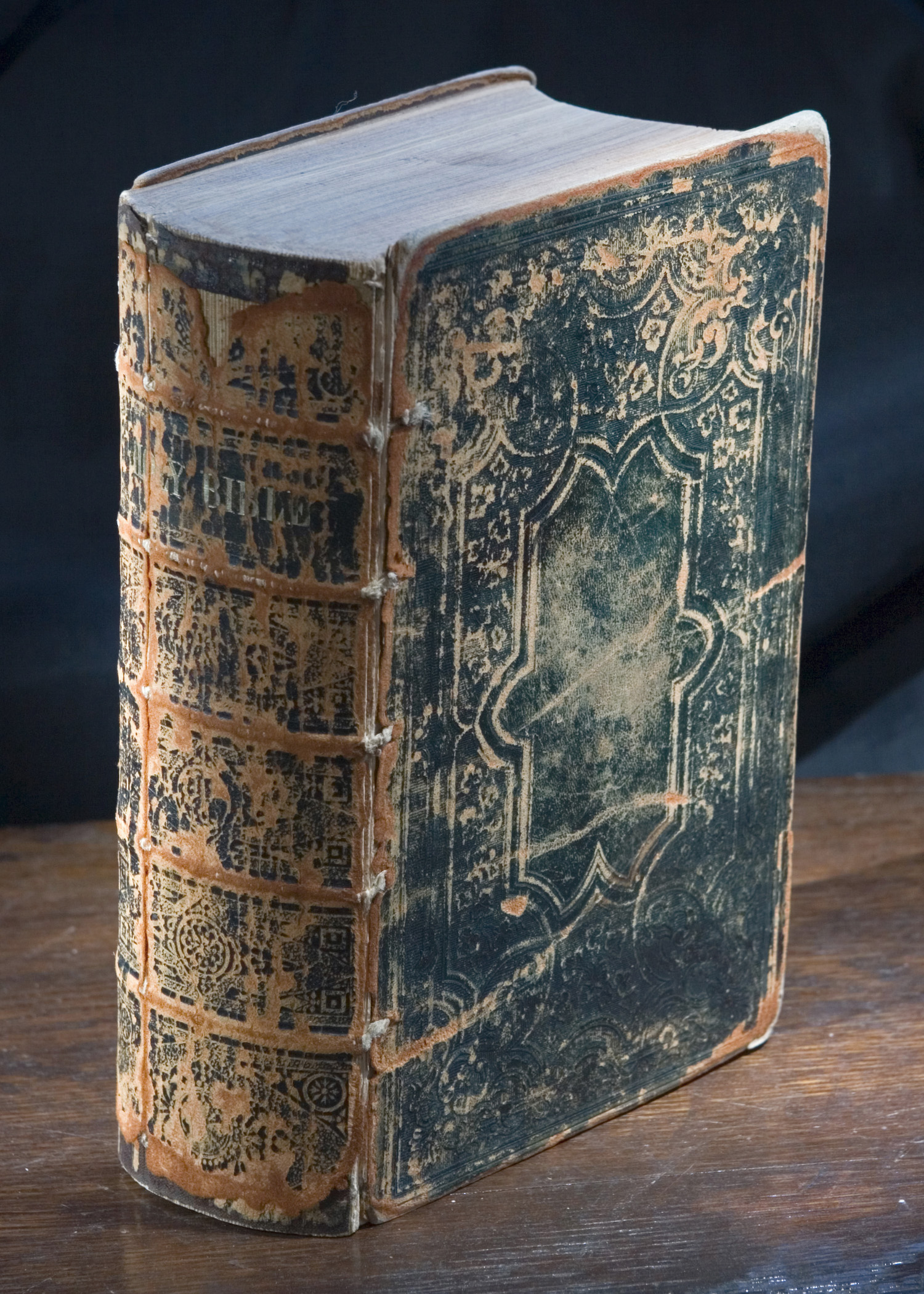

I'm done with "The Bible"

“Tradition is the democracy of the dead. It means giving a vote to the most obscure of all classes: our ancestors.”

David Ball - Original work

Like many Christians, I am a big fan of the Bible. It has it's flaws and it has its puzzles and a deep beauty that only can be described as sacred. However I am done with "The Bible". Not the actual sacred text of my faith tradition. Like I said, I am a fan of that. What I am done with is the phrase "The Bible".

Calling it "The Bible" while technically accurate leaves little to be desired theologically. What I mean by this is that when we hear "The Bible" we hear in our heads a dead set of stories. We hear a book. Or, putting it in the negative, when we hear "The Bible" we don't hear a living story. We don't hear lives of people. We don't hear this as a collection of stories giving witness to something indescribable that the characters do not fully understand but try to put words to because words are all we have.

Perhaps a better way to talk (and in turn think) about this collection of sacred stories is to shift talking about it as "The Bible" but as the "Biblical Witness". This collection of stories are the tradition of the people of faith and, as it has been said, tradition is the vote of the dead.

When we think about the Biblical Witness this begins to reshape the way we think about the sacred stories. We begin to think of these stories like that of a witness. And, like any witness, the Biblical witness has it's own biases and perspective and even errors. It is a valuable and powerful witness to God in the Christian faith tradition but, like I have argued before, it is not the ultimate revelation of God (that is reserved for Jesus). And so it is okay to admit that the Bible may have errors or inaccuracies or contradictions. It is a witness, it is not infallible nor inerrant.

And because the Biblical witness has the same biases and perspectives that other witnesses may have, it is important to know that the UMC affirms that there are other sources of authority that we use in conjunction with the Biblical witness to better discern the will and work of God. This is why the UMC holds fast to not only the Biblical witness but also, tradition, experience and reason.

Taken together, these four sources (perhaps we could call them the four witnesses?) are the voices we listen to in order to find what God desires and hopes and dreams. These four witnesses give us direction on how to live in right relationship with one another and with God and with ourselves.

It may not be helpful or reasonable to stop calling it "The Bible", but is it too much to expect that we can understand the Bible as bearing a living witness to the deep mysteries of God and not to understand the Bible as a set of dead stories of the past?

What words are your go to words?

Have you paid attention to the words a teacher uses over and over again in their speech? I am not talking about the verbal mnemonic devices employed, nor the words that function as fillers - like the works "like" or "um". I am talking about the words that the teacher uses time and time again that underpin the teachers overall philosophy?

Richard Rohr's book, Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi brought to light that Francis of Assisi used some words more than others. According to Rohr, "Those who have analyzed the writings of Francis have noted that he uses the word doing rather than understanding at a ratio of 175 times to five. Heart is used 42 times to one use of mind. Love is used 23 times as opposed to 12 uses of truth. Mercy is used 26 times while intellect is used only one time."

Doing, heart, love and mercy were, perhaps, Francis's go to words that functioned as his philosophical and theological underpinning. I understand that the sheer number of times a word is used does not mean this word is important. For instance, a political candidate may use the name of an opposing party more than they use their own but that does not mean they are secret members of the opposing party. Nonetheless, the frequency of words to the frequency of other words in a given teacher's lexicon is interesting.

There is this blog that makes word clouds of the different books of the Bible. And when you take a look at that you can begin to see some common themes. The first thing you may notice is how the Bible is often taught as a book about people and how to live - like a Christian version of Hammurabi's code or a moral document. However, the Bible's main protagonist is not humanity but God. This is a collection of books and stories written by people in order to try to put language and understanding around the indescribable and fully unknowable.

What words are your go to words? What do these words say about where your heart is? If someone were to examine all your writings what would your word frequency be for words like "love", "I", "welcome", "peace", "sorry", "forgiveness", "truth" or "joy"?

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.