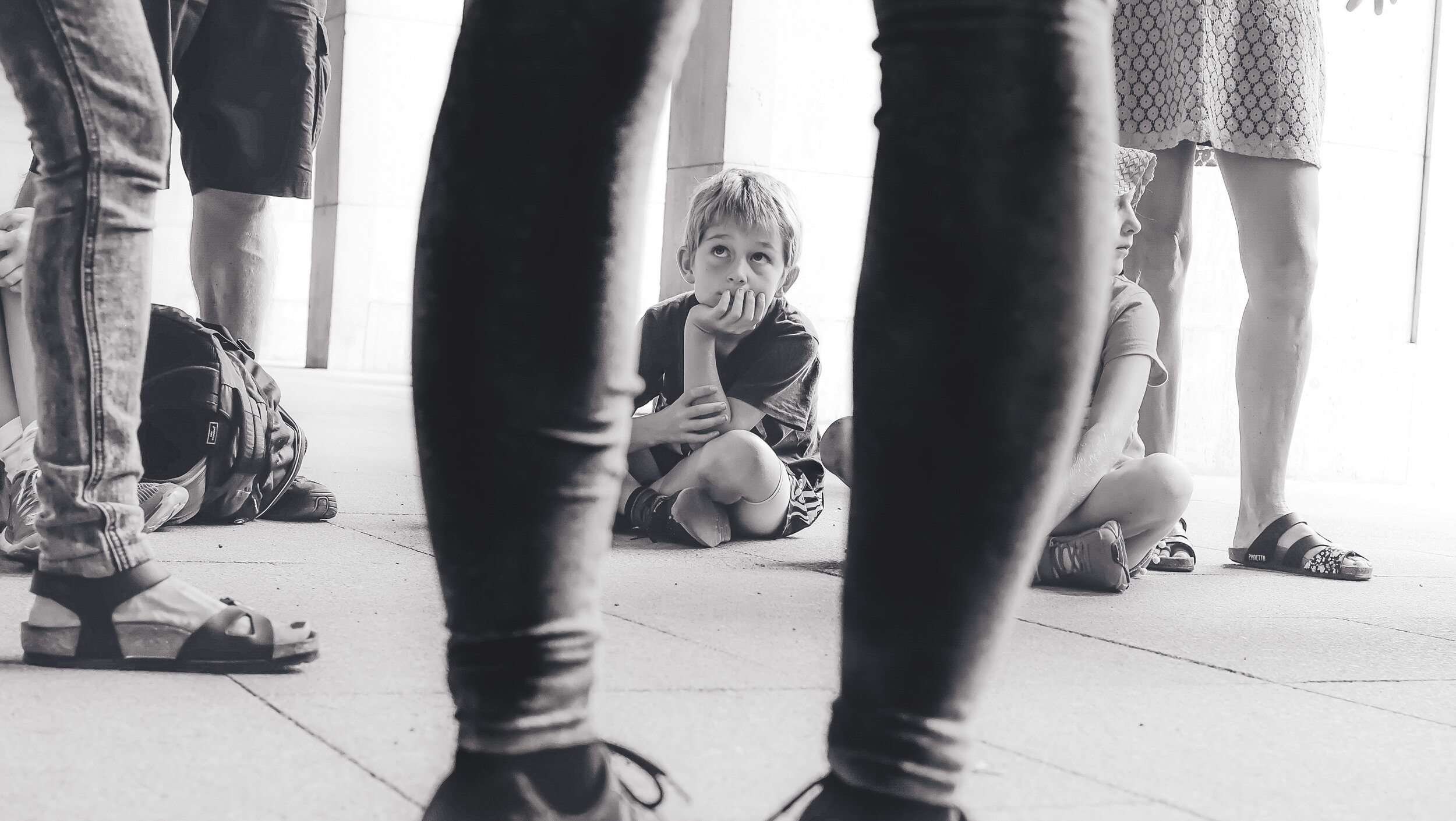

Learning From Observation Over Conversation

The Lives of the Desert Fathers by Norman Russell opens with this little story expressing why people would seek out holy men and women in the deserts of Egypt in order to learn from them:

We have come from Jerusalem for the good of our souls, so that what we have heard with our ears we may perceive with our eyes - for the ears are naturally less reliable than the eyes - and because very often forgetfulness follows what we hear, whereas the memory of what we have seen is not easily erased but remains imprinted on our minds like a picture.

Russell adds, that these pilgrims desired to learn from conversation with these desert sages, but more so pilgrims desired to learn from observation.

It is not deeply profound to be reminded that actions speak louder than words. It is not new that we best learn from doing rather than listening. And yet we continue in the Church to lean very heavily on the spoken word to teach others.

Preachers are important, but not in the ways that preachers think we are. Preachers are important not just for the words they say (the conversation) but through the lives we live. People listen to preachers who live lives that are compelling, interesting, different and authentic. For all the sermon classes and preaching tips I have taken, I have yet to be in such a training that elevates the life of the preacher over the words of the preacher.

That is, we preachers still elevate conversation over observation.

The truth is that conversation is easier than observation. Teaching by conversation does not require one to be open to the Spirit of resurrection. Teaching by observation does.

So take a look at the Church we serve. Many people are learning from us not by what we say in sermons or doctrine, but by observing our lives. Maybe God was onto something when it was proclaimed that God desires mercy and not sacrifice (Hosea 6:6, also echoed by Jesus in Matthew a few times). God desires mercy and compassion over the dogmatic and orthodox sacrifices that our religion demands.

Oddly enough, one does not have to know anything about religious practices to be merciful but you need to know a lot of religion to practice the proper sacrifices.

Learning through conversation is good. Observation is better.

Let Us Eat the Phlegm

in her book, The Desert Fathers: Sayings of the Early Christian Monks, Benedicta Ward translates the following story of our Christian desert teachers:

At a meeting of the brothers in Scetis, they were eating dates. One of them, who was ill from excessive fasting, brought up some phlegm in a fit of coughing, and unintentionally it fell on another of the brothers. The brother was tempted by an evil thought and felt driven to say, ‘Be quiet, and do not spit on me.’ So to tame himself and restrain his own angry thought he picked up what had been spat and put it in his mouth and swallowed it. Then he began to say to himself. ‘If you say to your brother what will sadden him, you will have to eat what nauseates you.’

In case you missed it, one brother coughed up phlegm onto a different brother who grew angry from being spat on. The spat upon brother chose to fight the internal battle of anger rather than say anything to the sick brother and possibly hurt him.

So he eat the phlegm.

My beloved denomination is sick. Many of us are spewing up all sorts of phlegm onto one another. We are become angry that someone would say something repulsive; that someone might act against the “code of conduct” and even the Book of Discipline - that someone might spread their “disgusting” theology. Too many of us become angry and choose to correct, embarrass or even reprimand another (always in the name of love).

I desire the heart (and stomach) to eat phlegm. I desire to address my inner conflict and anger knowing that is where the enemies last stand will be. Or in the spirit of another desert saying:

If anyone speaks to you on a controversial matter, do not argue with him. If he speaks well, say, “Yes.” If he speaks ill, say, “I don’t know anything about that.” Don’t argue with what he has said, and then your mind will be at peace.’

The world will be at peace not when we stop fighting, but when humanity is at peace with ourselves. For that internal peace will guide our actions toward one another. We do not have a denomination in conflict so much as the people that make up the Church are not at peace with our own selves. How do we overcome the internal anger and conflict within? Eat the phlegm.

Failing to Acquire the Fire We Desire

A few times a year I hear some variation of being on fire. Someone might say, “I was on fire for God after that experience.” Or perhaps giving voice to an aspiration one might say, “I want to be on fire for God.” Of course there is the idea that the church is too lame/boring/irrelevant and if only it were “on fire” then all would be right with the church. We talk about being on fire in all sorts of ways with the understanding that there is something overwhelmingly positive and admirable about being on fire.

However much we might long to be on fire, it seems that too many of us are not. How is it that we can desire something so deeply, so often, and so intensely but rarely acquire this fire we desire?

Photo by Siim Lukka on Unsplash

Amma Syncletica is one of the few desert mothers that we have some writings of. She puts her finger on perhaps why we are not on fire as often as we might desire:

“In the beginning there are a great many battles and a good deal of suffering for those who are advancing towards God and afterwards, ineffable joy. It is like those who wish to life a fire; at first they are choked by the smoke and cry, and by this means obtain what they seek (as it is said, Our God is a consuming fire - Hebrews 12:24). So we also must kindle the divine fire in ourselves through tears and heard work.” - Becoming Fire, Edited by Tim Vivian.

This saying has multivariate meanings to be sure but one of those is the pain, tears and work that is required on our parts to help foster the ignition of fire. Some of the smoke of practicing the disciplines is that they do not “produce” anything or that we might even feel silly doing them. Praying to God does not seem to make anything happen and we might even feel like it is magic thinking to talk to an ineffable and immeasurable God. So just as we begin to step away from the work of kindling the fire.

in our efforts to fully immerse ourselves in the waters of life, we might overlook that if we want to be on fire for God, that it is very difficult (if not impossible) for water-soaked wood to catch fire. Jesus had to go to the desert. The disciplines are often practices that draw us into emptiness (fasting, sabbath, giving, serving, etc.). The spiritual life might be thought of trying to dry us out so to catch fire. No wonder we are unable to acquire the fire we desire. Immersed in waters of business and novelty we are unable to dry out and catch the flame.

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.